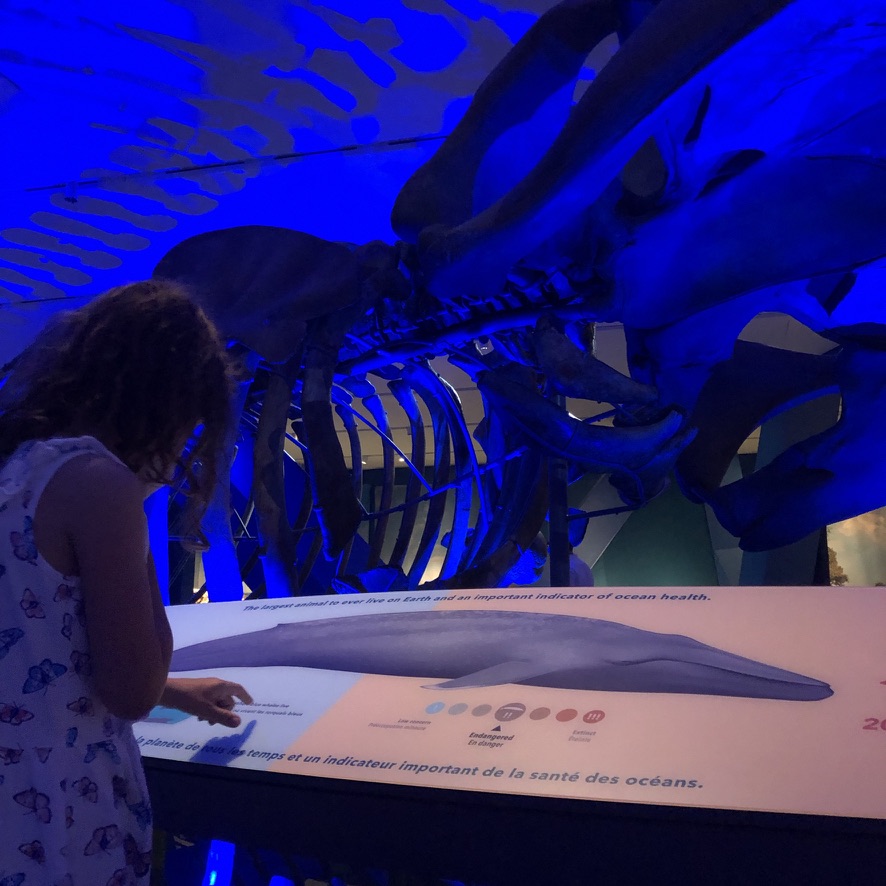

Imagine this…You and another family are planning a fun trip to the museum with your 7 year old kids, Lilah and Grey. There will be dinosaurs, interactive exhibits, a play area! What’s not to love? Once you arrive, you head to a new exhibit about whales. The exhibit is busy, loud but no big deal. Your child, Lilah, rushes between displays not really paying attention to what they are seeing. Your friend’s child, Grey, is asking questions, standing in front of a display for a few moments before moving on. You call out for Lilah to see a display but she doesn’t seem to hear you. You wander through the exhibit, trying to keep track of Lilah amidst all the people. After about 10 minutes, you hear complaining.

Lilah says she is tired. You dismiss her. We just got here, you say, let’s try seeing another exhibit. So you head to the dinosaur exhibit. Grey is super excited for dinosaurs. Lilah doesn’t seem to notice or care. When you arrive in the big dinosaur room, Lilah starts running around in the open space but sometimes running into people without realizing. You think, at least she is getting some energy out, but remind Lilah to watch her body and look around for other people. Grey is also energetic, but running to each exhibit to check it out. Lilah doesn’t seem to focus on anything in particular or be able to communicate clearly. After another 10 minutes, Lilah start complaining. She’s tired, she has a headache, she wants to go home. You dismiss her again. We only got here 20 minutes ago! We are here with our friends and we cannot leave after just 20 minutes!

Moving on into the next area of the museum, you visit the kids interactive play area. More people. More noise. More colours. More displays and lights. But where is Lilah? You start to panic looking through the immediate area. Suddenly you hear some raised voices coming from a closed off area calling out about a lost child. Lilah is found in a quiet spot – the baby nursing and feeding area. When you arrive, she is hiding in a fetal position a corner. She has her eyes closed tightly and hands over her ears. Lilah says she must go home now. She’s too tired to stay. You coax her out from the corner getting her to lie down on a bench. You try to reason with her: We are trying to enjoy the afternoon with our friends. We’ve only been here 30 minutes! We are not leaving yet. But Lilah is done. She’s in full shutdown mode.

Lilah clearly struggles in busy, overstimulating environments such as a museum. Many kids do. Some parents would avoid busy overstimulating environments however that is not real life. Also why should Lilah not experience a museum with a friend just because she gets overstimulated and shuts down? Perhaps there is another way to handle this situation.

If you need more information about overstimulation and meltdowns, then check out the Meltdowns happen post here. If you want to know more about what neurodivergence is, I have more details in this post.

Do you know any museums that are neurodivergent kid friendly? Please leave comments below to share your knowledge for others. Also check out https://theneurodiversemuseum.org.uk who have far more information that my OT Living with Kids experience. Navigating a child’s big emotions and behaviours can be very challenging as a parent. If needed, please seek the support of an OT or psychologist. Speak with your doctor. Here are a few of my general tips and tricks:

How to plan a trip to a museum with a child who is neurodivergent:

Museums are often built to be immersive, interactive, sensory experiences to help teach and interpret information. A huge amount of time and money are invested into these spaces to translate the museum’s knowledge to the public. Visiting a museum with a child (or another adult) who is neurodivergent requires a bit of planning and preparation, but can have long-standing impact on that person’s life.

- Plan in advance.

- Check out the museum website. Some museums have developed policies helping any visitor with neurodivergence. Dedicated visitor hours are quieter, have fewer people admitted and are less stimulating (e.g. lights not too bright or too dim, noise levels lower) to ensure a more positive experience. Some museum have designated areas where people can decompress.

- Arrive early. Ideally at opening and try to leave within the first 2 hours of opening as museums often get busier later in the day.

- Plan breaks. How often you break will depend on your child so follow your child’s lead. If you need to pause somewhere quiet for a few minutes every 10 minutes, then do that. Or perhaps you can do one exhibit, then break for a snack. If allowed, you can go outside for a moment and return.

- Since I mentioned snacks…Plan snacks. Museums typically have designated areas for eating, please respect those spaces. But bring water and foods your child will reliably eat. It’s hard to understand whether your body is thirsty or hungry when you are overwhelmed. Keeping thirst and hunger in check will keep your visit going.

- Help accommodate the environment for your child.

- Is noise a problem? Bring noise cancelling headphones. Does your child need deep pressure? Have them wear tight, layered clothing can sometimes provide compression. Tell you child they can have hug breaks from you if they need.

- What other strategies calm your child? Some ideas include: Chewing gum, straw water bottle, fidget toy. Every child is different so this may take some trial and error or expertise from an OT to figure out.

- You, as their parent, are a big calming force in your child’s life. Communicate in advance with your child about the day. Set the stage so they can tell you when they are overwhelmed or need a break. For those little ones who do not have insight into their challenges, you can learn when they are getting overstimulated. Before shutdown (or meltdowns) happen, you can jump in.

- Check in with your own expectations. You may recall visiting museums for a ½ or full day as a child, but that may not be your child’s reality. Stay flexible. Keep expectations low.

- Communicate with any friends or family members that are coming with you what your plans are and any strategies you may need e.g. arriving early, taking breaks.

- Here is also an example of an excellent document developed by the Tower of London, which helps anyone with neurodivergence plan their visit

Obviously, planning in advance is easier to do if you know your child may struggle in a busy, overstimulating environment. If you ran into trouble during your visit, keep reading…

My child is overstimulated, melting down or shut down, now what?

- This situation can be very stressful and typically occurs after a child was overstimulated or struggling in some way, then escalates.

- First ensure your child’s safety.

- Once safe to do so, take a deep breath. Try to stay calm. Your child does not know what they are doing is unusual or atypical unless they have been told or have insight into their behavior. They are responding to their body’s needs. You staying calm helps them and everyone around you regulate too. If you cannot stay calm, just be honest with yourself and ask for help. Trading off with another parent or friend can be helpful.

- Do not reprimand a child. Compassion and empathy are needed. Your child may not even be able to communicate with you in the moment. That is ok. Communication is very hard when you or your child are stressed. Perhaps you have other kids in tow and they are also misbehaving. Do the best you can in the moment and give yourself grace if you mess up.

- Remind yourself – it is not your child’s fault, it is not your fault. Even with the best laid plans and expectations, you may not be able to do what you hoped at the museum.

- Bring your child to a quieter location with less distraction. Give them time to get out emotion or regulate. The amount of time they need will depend on the child.

- Ask for help from a museum staff member.

- Follow up later with the child. Have a short age-appropriate chat once they have calmed down. That could be later in the day or the next day. The follow up chat can help a child build insight by labelling what you saw happen. E.g. “I noticed you seemed very hyper when we were in the dinosaur exhibit. How was your body feeling?” You are helping a child learn how to navigate these big emotions and behaviours.

- If a child is very young or preschool age, then they may need some time to mature. Try again in a year or two when they are a bit older.

Remember that going to a museum is a learning experience. For some children, their museum learning includes handling an overwhelming environment. That is ok. It’s a crucial life skill that some children need. In some cases, they will have to try out this skill many, many times before they learn. They will never be able to learn anything else in the museum until their body is regulated and calm.

In my opinion, museums need to be neurodivergent-friendly. I’ve had success providing feedback through electronic after-visit surveys or directly emailing feedback. Keep any feedback constructive and solution-focused. You may be surprised getting a response back!

Lastly, I have been amazed at what my child remembers from a museum visit. When my memory may be of a stressful, horrible time, the child’s memory may be very different. Yes, they know they had a bad moment, but they got to do something new, different, maybe they remember having fun! So don’t assume your bad experience is their experience. Going to a museum with a child who is neurodivergent requires additional time and effort on the parent’s part. But that extra effort might just pay off and help your child have more museum trips in the future.